Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, is a very terrifying day. While it is an opportunity to start again through confession and regret, there is a sense of urgency that highlights the day. Whether one has spent this time preparing or not, how can a person wipe the entire slate clean in one 25 hour period? Sure, change is ultimately instantaneous, yet in examining the liturgy of the day, the task of repentance and finding forgiveness seems insurmountable.

Throughout Yom Kippur, the liturgy revolves around a formal confession, viddui, which lists a litany of areas we encounter and inevitably fall short of during the year. I find myself overwhelmed by the vastness of our perceived imperfections and our forced listing of them again and again. It can be lonely when confronting one’s shame, one’s failures. How can we even open our mouths to recite these words? It can be too much!

Yet, there is a short phrase in the introduction of the viddui which brings me solace. Before reciting the confession, it says:

אֱלֹהֵֽינוּ וֵאלֹהֵי אֲבוֹתֵֽינוּ תָּבֹא לְפָנֶֽיךָ תְּפִלָּתֵֽנוּ, וְאַל תִּתְעַלַּם מִתְּחִנָּתֵֽנוּ שֶׁאֵין אֲנַֽחְנוּ עַזֵּי פָנִים וּקְשֵׁי עֹֽרֶף לוֹמַר לְפָנֶֽיךָ יְהֹוָה אֱלֹהֵֽינוּ וֵאלֹהֵי אֲבוֹתֵֽינוּ צַדִּיקִים אֲנַֽחְנוּ וְלֹא חָטָֽאנוּ אֲבָל אֲנַֽחְנוּ וַאֲבוֹתֵֽינוּ חָטָֽאנוּ:

Our God and God of our fathers, let our prayer come before you and do not ignore our supplication. For we are not so brazen-faced and stiff-necked to say to you, Adonoy, our God, and God of our fathers, “We are righteous and have not sinned.” But, indeed, we and our fathers have sinned.

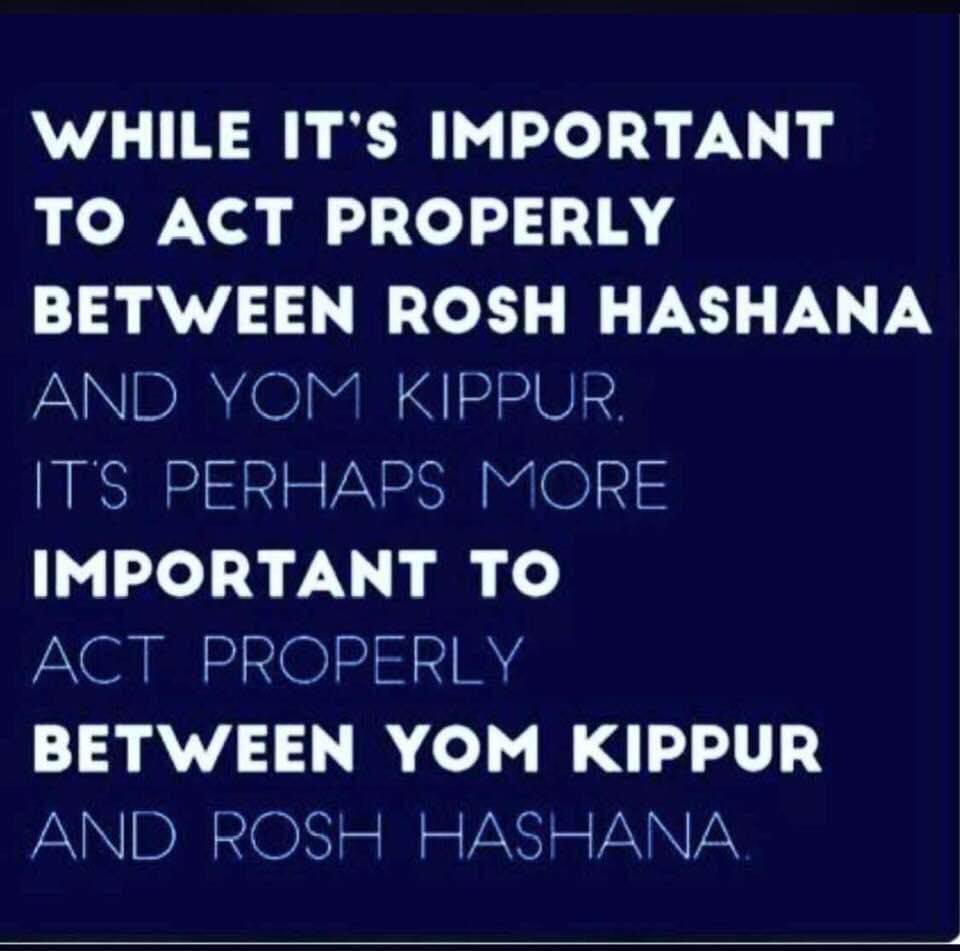

When we are confronting our inner self, working to overcome aspects of our lives we wish to change for the better, confessing our imperfections, there is a sense of being alone. And yet, in this phrase, “But, indeed, we and our fathers have sinned” the prayer is offering us strength, in that we are not alone in this process. We enter the auspicious day as part of a chain of tradition. We are here because it is part of our tradition, our legacy, to pause and take stock of what we have fallen short of and what we hope to rise to in the coming year. We are here because our parents, grandparents, etc. also needed a day a year to reframe life’s challenges and struggles. We are not doing this because everyone else is perfect and we are not. Rather, Yom Kippur is a day for all of us to embrace the imperfections for it is through this embrace that we can grow.

One of the struggles with growth and change in life is thinking that those around us don’t understand the struggles we are dealing with. When people are honest about their fears, worries and doubts, many barriers to change are removed. (As an example of a book that speaks about how shame is a barrier to change, see The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You’re Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You Are by Brene Brown.)

As we prepare in these final hours for Yom Kippur, may we find the resolve of knowing that we are all striving to be our ideal selves and find ways of reaching for those ideals. And if we fall short, if we err, let us remember that its OK, its part of our being human. It is merely a lonely struggle but it is a struggle we all face. May this Yom Kippur be a day of meaning, a day of introspection and a day of finding something to strive to reach for in the coming year.