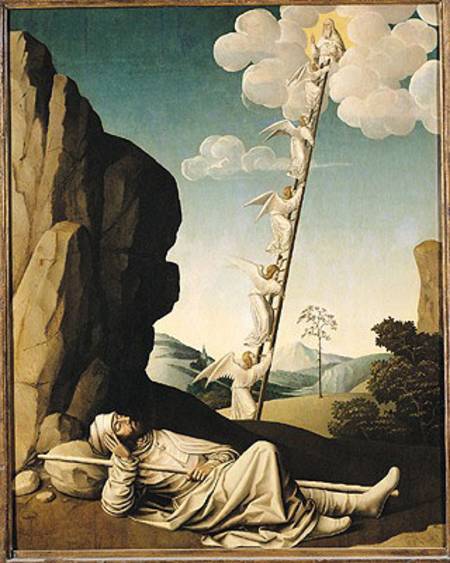

When life thrusts uncertainties at us, we often grasp for a sense of being connected to someone or something. We search for ways to recreate the sense of safety and certainty, either consciously or not. This idea of looking for refocusing on how faith and belief might be a place of safety is exemplified in one of the famous biblical stories, Jacob’s dream in which he envisions a “Stairway to Heaven.”

After running away from Isaac and Rebecca’s home as a means of self preservation because his twin brother Esau planned to take revenge over the stolen birthright, the Torah finds Jacob having stopped overnight to sleep. On this night, Jacob dreams of a ladder going from the land to heaven. The Torah states:

וַֽיַּחֲלֹ֗ם וְהִנֵּ֤ה סֻלָּם֙ מֻצָּ֣ב אַ֔רְצָה וְרֹאשׁ֖וֹ מַגִּ֣יעַ הַשָּׁמָ֑יְמָה וְהִנֵּה֙ מַלְאֲכֵ֣י אֱלֹהִ֔ים עֹלִ֥ים וְיֹרְדִ֖ים בּֽוֹ׃

He had a dream; a ladder was set on the ground and its top reached to the sky, and angels of God were going up and down on it.

וְהִנֵּ֨ה יְהֹוָ֜ה נִצָּ֣ב עָלָיו֮ וַיֹּאמַר֒ אֲנִ֣י יְהֹוָ֗ה אֱלֹהֵי֙ אַבְרָהָ֣ם אָבִ֔יךָ וֵאלֹהֵ֖י יִצְחָ֑ק הָאָ֗רֶץ אֲשֶׁ֤ר אַתָּה֙ שֹׁכֵ֣ב עָלֶ֔יהָ לְךָ֥ אֶתְּנֶ֖נָּה וּלְזַרְעֶֽךָ׃

And the LORD was standing beside him and He said, “I am the LORD, the God of your father Abraham and the God of Isaac: the ground on which you are lying I will assign to you and to your offspring.

וְהָיָ֤ה זַרְעֲךָ֙ כַּעֲפַ֣ר הָאָ֔רֶץ וּפָרַצְתָּ֛ יָ֥מָּה וָקֵ֖דְמָה וְצָפֹ֣נָה וָנֶ֑גְבָּה וְנִבְרְכ֥וּ בְךָ֛ כל־מִשְׁפְּחֹ֥ת הָאֲדָמָ֖ה וּבְזַרְעֶֽךָ׃

Your descendants shall be as the dust of the earth; you shall spread out to the west and to the east, to the north and to the south. All the families of the earth shall bless themselves by you and your descendants.

וְהִנֵּ֨ה אָנֹכִ֜י עִמָּ֗ךְ וּשְׁמַרְתִּ֙יךָ֙ בְּכֹ֣ל אֲשֶׁר־תֵּלֵ֔ךְ וַהֲשִׁ֣בֹתִ֔יךָ אֶל־הָאֲדָמָ֖ה הַזֹּ֑את כִּ֚י לֹ֣א אֶֽעֱזָבְךָ֔ עַ֚ד אֲשֶׁ֣ר אִם־עָשִׂ֔יתִי אֵ֥ת אֲשֶׁר־דִּבַּ֖רְתִּי לָֽךְ׃

Remember, I am with you: I will protect you wherever you go and will bring you back to this land. I will not leave you until I have done what I have promised you.”

Genesis 28:12-16

Jacob dreams/receives a prophetic message that Gd will be with him and protect him throughout his journey until such time as he returns to the land of Canaan. For Jacob, this reassurance is key to his ability to withstand the trials and tribulations he will come to face during his sojourn. Yet, Jacob maintains uncertain, for a few verses later, as Jacob takes leave of this seemingly holy place, the Torah states:

וַיִּדַּ֥ר יַעֲקֹ֖ב נֶ֣דֶר לֵאמֹ֑ר אִם־יִהְיֶ֨ה אֱלֹהִ֜ים עִמָּדִ֗י וּשְׁמָרַ֙נִי֙ בַּדֶּ֤רֶךְ הַזֶּה֙ אֲשֶׁ֣ר אָנֹכִ֣י הוֹלֵ֔ךְ וְנָֽתַן־לִ֥י לֶ֛חֶם לֶאֱכֹ֖ל וּבֶ֥גֶד לִלְבֹּֽשׁ׃

Jacob then made a vow, saying, “If God remains with me, if He protects me on this journey that I am making, and gives me bread to eat and clothing to wear,

וְשַׁבְתִּ֥י בְשָׁל֖וֹם אֶל־בֵּ֣ית אָבִ֑י וְהָיָ֧ה יְהֹוָ֛ה לִ֖י לֵאלֹהִֽים׃

and if I return safe to my father’s house—the LORD shall be my God.

וְהָאֶ֣בֶן הַזֹּ֗את אֲשֶׁר־שַׂ֙מְתִּי֙ מַצֵּבָ֔ה יִהְיֶ֖ה בֵּ֣ית אֱלֹהִ֑ים וְכֹל֙ אֲשֶׁ֣ר תִּתֶּן־לִ֔י עַשֵּׂ֖ר אֲעַשְּׂרֶ֥נּוּ לָֽךְ׃

And this stone, which I have set up as a pillar, shall be God’s abode; and of all that You give me, I will set aside a tithe for You.”

Genesis 28:20-22

This latter scene suggests that Jacob was not one hundred percent convinced that Gd would fulfill his promise from the dream, so Jacobs offers the vow that he would provide a percentage of his hoped for accumulated wealth to Gd as a tribute for protection. Why would Jacob not believe wholeheartedly in Gd’s promise? I would suggest that Jacob’s uncertainty is not from a lack of faith but rather from an innate sense of abandonment that he feeling on this night. This is depicted in the first image of the dream, in which the “angels of Gd” ascend and then descend from the ladder. If we consider the image we would expect to see, the angels should have descending first and only then ascending. Yet, the verse flips the actions, leading to the following comment from Rashi:

עלים וירדים ASCENDING AND DESCENDING — It states first ascending and afterwards descending! Those angels who accompanied him in the land of Israel were not permitted to leave the Land: they ascended to Heaven and angels which were to minister outside the Land descended to accompany him (Genesis Rabbah 68:12).

As we know, dreams, even in the prophetic sense that is attributed to them throughout the Bible, contain many images that illustrate our unconscious or conscious concerns. For Jacob, the angels were his protectors, his internal sense of not being alone, which his subconscious highlighted in his vision. While Jacob does have a destination, his uncle’s home and a mission to marry his uncle’s daughter, he is presumably filled with feelings of abandonment and uncertainty about the future. As such, he dreams of angels first ascending, for deep down he knows he is never alone. Furthermore, the entire dream focuses on Gd being with him throughout his journey. The angels represent that Jacob can rest assured that he is not being abandoned at any point.

Regarding his vow after the dreams, the vow speaks to Jacob’s conscious sense of uncertainty. A dream is a dream and even one of a “prophetic” nature can leave someone with doubts. Jacob’s vow/covenant to Gd is a way for Jacob to accept that dream and change his mindset. No longer will he allow himself to be worried about the uncertainties that lie ahead. He knows he will be able to handle them because of Gd’s “promise” and his offer as a means of submission to this new perspective.

Jacob’s vision and response is a powerful example of the challenge we all face when starting on a new journey. Deep down we know there is risk any time we venture into something new. Doubts exist. Yet, if we allow the doubts to overtake us, we will never be able to take the first step. When we acknowledge the doubts and take control of them, recognizing the doubts are part of the journey, not the barrier, we will be able to move forward and find our new beginning.

May we find the ability to change our mindset as we work towards achieving our growth potential and our wishes.