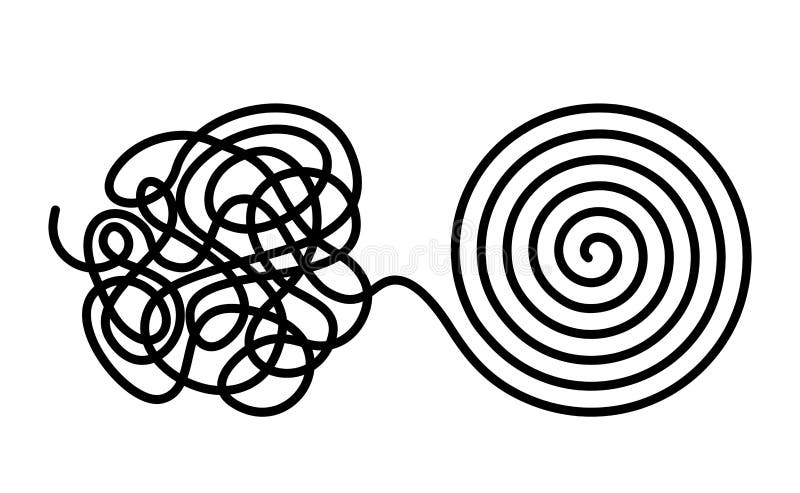

The title of this post was inspired by my wife’s comment to yesterday’s piece, From Despair to Hope: Seven Weeks until Rosh Hashanah. Each day, we have the opportunity to do something that helps foster a feeling of onward and upward. Too often we remain in the despair, the stagnant place of not doing. There could be many reasons for the paralysis. We are afraid, we hate making a mistake or mistakes, we don’t want to fail. Or perhaps we are really in a place where progress is almost impossible to foster (and we need the support of professionals to help and support us in these darker moments.)

How do we foster the ability to go onward and upward?

Forward momentum begins from a place of taking stock. If we spend the time in introspection, in reflecting on our journeys, we will begin to see how far we have come. We have taken the step/s forward we intended on the way to attaining our goals. Yet, too often, as I have been writing about lately, we don’t recognize how we got this moment, but will only look at how far we still want or need to go. My personal growth and journey continuously includes the work of seeing what I have accomplished along the way, not as a means of resting on my past but as a way of drawing strength from what was to continue to take one step at a time. Every step is an achievement unto itself. By celebrating the results, regardless of “success” or “failure,” we can learn to find real success, which is the striving forward we all look for in our lives.

A primary element of the period leading into Rosh Hashanah is the preparation for the aspect of Rosh Hashanah that is Gd judging the world for the upcoming year. This preparation is usually described as Teshuva, normally translated as repentance but better translated as a type of returning. In the words of Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson o.b.m. as presented by Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks o.b.m:

2. Teshuvah and Repentance

“Repentance” in Hebrew is not teshuvah, but charatah. Not only are these two terms not synonymous, they are opposites.

Charatah implies remorse, or a feeling of guilt about the past and an intention to behave in a completely new way in the future. The person decides to become “a new man.” But teshuvah means “returning” to the old, to one’s original nature. Underlying the concept of teshuvah is the fact that the Jew is, in essence, good. Desires or temptations may deflect him temporarily from being himself, being true to his essence. But the bad that he does is not part of, nor does it affect, his real nature. Teshuvah is a return to the self. While “repentance” involves dismissing the past and starting anew, teshuvah means going back to one’s roots in G‑d and exposing them as one’s true character.

For this reason, while the righteous have no need to repent, and the wicked may be unable to, both may do teshuvah. The righteous, though they have never sinned, have to constantly strive to return to their innermost. And the wicked, however distant they are from G‑d, can always return, for teshuvah does not involve creating anything new, only rediscovering the good that was always within them.

What resonates most for me is that by seeing Teshuva as a focus on the idea of returning to one’s spiritual roots instead of seeing the time as one we spend reflecting on all we haven’t accomplished, we can find the strength to truly go onward and upward.

Today is the second day along the seven week path towards Rosh Hashanah. What will your “return to self” look like? How will you work on taking the steps you are taking in your lives and further fostering growth and change to better oneself in this life?

Looking for help along your journey as you go onward and upward? Contact New Beginnings Spiritual Coaching and Consulting LLC at 732-314-6758 ext. 100 or via email at newbeginningsspiritualcoach@gmail.com.