Death is the inevitable conclusion of life. Perhaps we could even go so far as to suggest that death always accompanies us. While this is a morbid outlook, suggesting a life in which we are constantly looking over our shoulder for the Angel of Death to tap us as “next,” the recognition of our impermanence is also a prime driver to our continued striving to live life fully. Regardless of whether the recognition of death has a positive or negative impact, death being a constant in life is practically unavoidable. (This is not the same as embracing death as a good. This is acknowledging a fact we must also encounter).

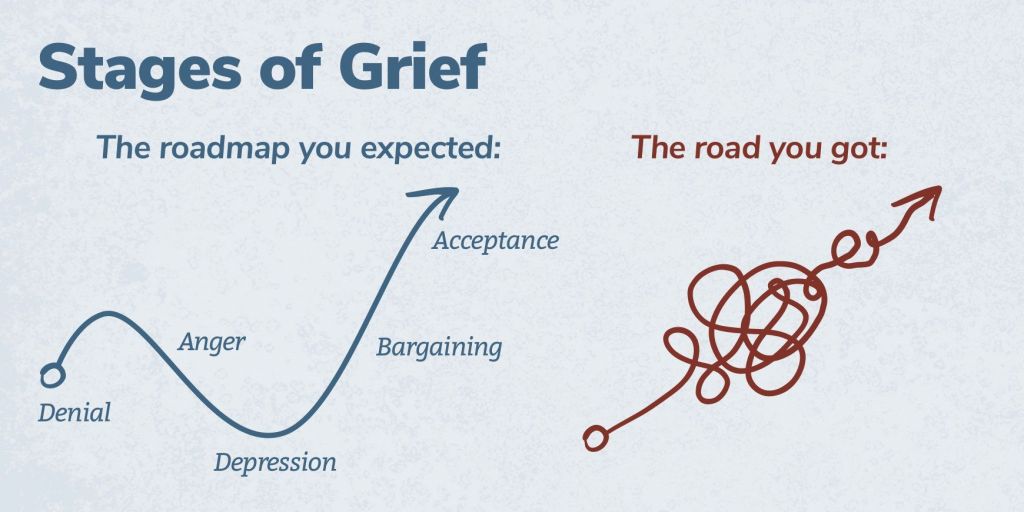

As much as death is a part of life, grieving is the natural response to death. Grieving is the experience of an opening of the emotional floodgates. We might even suggest that grieving is the merging of all emotions. People are angry, sad, guilt-ridden, and also relieved, content, and serene in the face of death. We can and do experience all these emotions at times after the death of someone important to our lives. The complexity of our emotions can be overwhelming. The challenge is embracing all of these emotions in a way that allows us to integrate the change that death causes in our lives. I believe that one of the major struggles we face in mourning a loved one is the internal struggle we experience because we don’t like feeling out of sorts that result from the onslaught of thoughts, images and emotions we face. As such, we try to “ignore” them or fight against them. In my experience, this struggle is often part of what underlies the sense people have of not “moving on,” “getting better,” etc.

With this premise, I want to add my perspective to the recent discussion about the inclusion in the DSM-5 (here) of a new diagnosis called “prolonged grief disorder (for a working definition, see here).” This diagnosis was debated in a recent article in the New York Times, How Long Should It Take to Grieve? Psychiatry has come up with an answer (NYT link). According to the article, prolonged grief disorder would apply to anyone who is “incapacitated, pining and ruminating after a year of loss, and unable to return to previous activities.” The issue of providing a timeframe has been the center of much debate within the greater debate about whether “complicated” grief should be considered a mental disorder, instead of being seen as a “fundamental aspect of our human experience.”

In reflecting on prolonged grief, I was reminded of a topic that has fascinated me for years. Many write about grief and mourning in a theoretical manner and the in a different way when describing the personal experience. One version of this which I would like to offer is the story of Maimonides and his experience of his brother’s death. Maimonides, the great 12th century Rabbi and Jewish thinker, in his laws of mourning, wrote the following:

אַל יִתְקַשֶּׁה אָדָם עַל מֵתוֹ יֶתֶר מִדַּאי. שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר “אַל תִּבְכּוּ לְמֵת וְאַל תָּנֻדוּ לוֹ”. כְּלוֹמַר יֶתֶר מִדַּאי שֶׁזֶּהוּ מִנְהָגוֹ שֶׁל עוֹלָם. וְהַמְצַעֵר [עַצְמוֹ יוֹתֵר] עַל מִנְהָגוֹ שֶׁל עוֹלָם הֲרֵי זֶה טִפֵּשׁ. אֶלָּא כֵּיצַד יַעֲשֶׂה. שְׁלֹשָׁה לִבְכִי. שִׁבְעָה לְהֶסְפֵּד. שְׁלֹשִׁים יוֹם לְתִסְפֹּרֶת וְלִשְׁאָר הַחֲמִשָּׁה דְּבָרִים:

One should not grieve too much over his deceased relative, as it is written : “Weep not for him who is dead, wail not over him” (Jeremiah 22:10); that is, weep not for him too much, since this is the way of the world. He who grieves too much over what is bound to happen is a fool. What measure of mourning should one follow? Three days for weeping, seven for lamenting, thirty days for abstaining from a haircut, and the rest of the five things.

Mishneh Torah – Hilkhot Avel 13:11

Maimonides, in essence, is proposing a time frame and window in which “grieving” is normal. From a purely ritualistic and theoretical perspective, this statement should is a prescription for mourning. His premise is; considering death is inevitable to life, why should we get bogged down for too long in sadness. It seems foolish. Yet, before judging the above, there is another side to Maimonides. While Maimonides the legal scholar is offering a prescription to “normal” grief, in a letter Maimonides wrote to a judge by the name of Yefet, we meet Maimonides the person:

“A few months after we departed from [the Land of Israel], my father and master died (may the memory of the righteous be a blessing). Letters of condolences arrived from the furthest west and from the land of Edom…yet you disregarded this. Furthermore, I suffered many well-known calamities in Egypt, including sickness, financial loss and the attempt by informers to have me killed.

The worst disaster that struck me of late, worse than anything I had ever experienced from the time I was born until this day, was the demise of that upright man (may the memory of the righteous be a blessing), who drowned in the Indian Ocean while in possession of much money belonging to me, to him and to others, leaving a young daughter and his widow in my care. For about a year from the day the evil tidings reached me I remained prostrate in bed with a severe inflammation, fever and mental confusion, and well nigh perished.

From then until this day, that is about eight years, I have been in a state of disconsolate mourning. How can I be consoled? For he was my son; he grew up upon my knees; he was my brother, my pupil. It was he who did business in the marketplace, earning a livelihood, while I dwelled in security. He had a ready grasp of Talmud and a superb mastery of grammar. My only joy was to see him. “The sun has set on all joy.” [Isa. 24:11.] For he has gone on to eternal life, leaving me dismayed in a foreign land. Whenever I see his handwriting or one of his books my heart is churned inside me and my sorrow is rekindled… And were it not for the Torah, which is my delight, and for scientific matters, which let me forget my sorrow, “I would have perished in my affliction” [Ps. 119:92].

https://jewishlink.news/features/26304-a-letter-from-rambam-about-the-death-of-his-brother-david

The same man who wrote about limiting one’s grief might also be a prime example of “prolonged grief disorder” as diagnosed today. I would be hard pressed to prove this “diagnosis.” Simply put, to reconcile Maimonides the scholar and Maimonides the person is that from a legalistic perspective the ideal is to follow the prescribed ritual as a means of guiding one through grief. Even his harsh comment in which he suggests that the one who excessively mourns is a fool is perhaps a statement imploring people to realize that ritual used effectively must have boundaries and be limited. Yet, in the lived experience, this is neither easy nor what most experience.

To conclude, I would suggest this insight from Maimonides theoretical vs. lived experience can be a guide in thinking about the phrase of “Prolonged Grief Disorder.” The challenge of diagnosing grief as a “disorder” because of action/inaction after a certain period is that for many, the real grief journey doesn’t truly begin until after a year has past. I believe this to be the case because it is only after having cycled through a year and all the events of the year that one has experienced the loss in its various iterations. The question is how does one live in the midst of this new reality. How does a person integrate the death into one’s life? Throughout the first year post death, we are encountering a life without the person, both in our day to day living and during the big moments, holidays, celebrations, etc. After going through this cycle once, the majority should find the emotional pain less acute both in the day to day as well as during these moments. The sadness will remain. The empty chair/s will always remain. The DSM diagnosis is not rejecting that our emotional response to death won’t remain with sadness, tears, etc. It is a functional diagnostic coding tool to extend mental health care to those who experience difficulty in the transitions that grieving should offer in integrating the death into the life we want to continue living.

If you or someone you know is experiencing challenges related to grief and loss: Contact New Beginnings Spiritual Coaching and Consulting LLC at 732-314-6758 ext. 100 or via email at newbeginningsspiritualcoach@gmail.com